Revolt in the Streets

Asiaweek, August 19, 1988.

At 6:10 a.m. on Aug.6, a huge earthquake began to rumble deep below Burma's far north. Measuring 7 on the Richter scale -- the biggest in the region for more than three decades -- it rocked buildings in Burma, Bangladesh and northeastern India and sent seething swells down rivers, tipping up over crowded ferries. The tremors that reached Rangoon were not enough to deflect the building protest against Burma's new iron fisted leader, Sein Lwin. But the superstitious strong man likely saw some kind of portent. The event seemed almost too coincidental with the massive upheavals that were to shake the country several days later, the most violent and widespread disturbances since his predecessor Ne Win's takeover 1n 1962.

Aug. 8 was the day dissatisfied students planned a nationwide strike. It is not clear why the chose the date. There is historical significance for Burmese in the all eights date: a kingdom fell in the year 888 (16th Century) in the Burmese calendar. It didn't happen on this day. The strike call went largely unheeded in Rangoon, partly because of heavy troop deployment at key buildings. Some shops and streetside stalls downed shutters but most businesses went on as usual and government offices closed only temporarily.

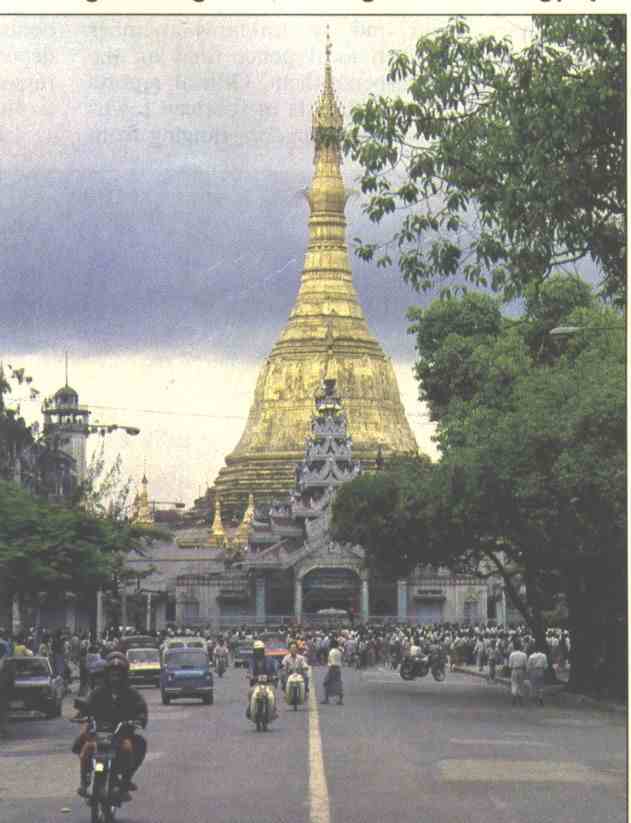

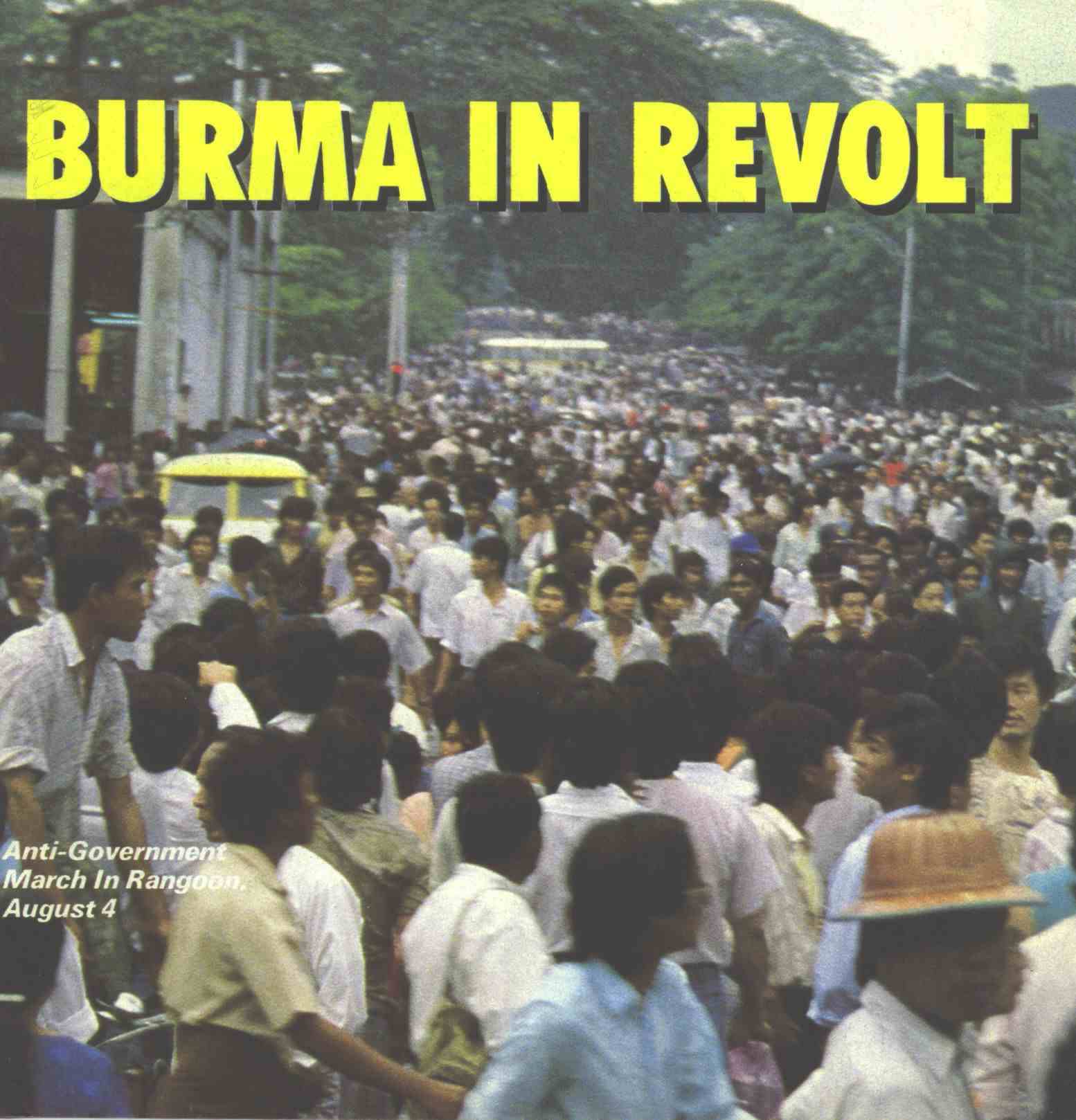

The boycott may not have come off, but people clustered in the streets of the capital despite the bristling presence of soldiers with automatic weapons and shot guns. Particularly well-guarded were City Hall and the Sule and Shwedagon pagodas, all landmarks where earlier protests had centered. Unofficial estimates put the crowd in central Rangoon at more than 5,000. The atmosphere, initially, was almost festive. Demonstrators waved banners, chanted and sang protest songs. That evening, however, they did not disperse. As the night wore on, the scene became ugly.

The state radio account has it that at 2 a.m. the mob went on the rampage, smashing traffic lights, windows and car windscreens. Seven hours later, it reported security forces fired warning shots and then a volley of fire into a crowd. Diplomats sad that the incident took place around a student resthouse near the Shwedaton, which is Burma's most sacred shrine. People living in the vicinity of City Hall claimed that many protesters had gun shot wounds. The official provisional toll for the capital over the two days was five dead, 55 wounded and 1,451 arrested, but unofficial accounts indicate many more casualties. At the same time, reports were coming in off violence throughtout Burma.

State radio said that 31 people had died when police fired on a crowd of 5,000 converging on a police station at Sagaing, 560 km north of Rangoon. Unofficial estimates reckoned the number of deaths country wide at 100.

Rangoon went into emergency isolation. Some foreign embassies closed their doors As the danger mounted. Instructions went out to Burma's own emissaries abroad to stop issuing tourist visas. At mid-week, Rangoon remained tense. Said a visitor coming out of the strife torn capital on Aug. 10, "Everywhere in town there are military and the roads are partly blocked." The outbursts against the government, which trace their immediate origin to student protests again the demonetisation of large-denomination banknotes in September last year, had spread to more and more centres outside the capital. Clearly, after months of smouldering resentment, Burma was in open revolt.

The latest wave of unrest came in the wake of martial law regulations imposed on Aug. 3 in 24 townships in Rangoon Sein Lwin, 64, signed the official proclamation himself just a week after he became president. The decree stated that a situation had arisen which the original organs of power could no longer control. Maj-Gen. Ye Nyunt, head of the Rangoon command, was put in charge of administering military rule which, under Burma's constitution, has no time limit and can be revoked only by the State Council.

The restrictive order was apparently prompted by a protest of young men, mainly students, in Rangoon that day. Officially, they numbered 200 but eyewitnesses reckoned there were 5,000 to 10,000 of them. Headed by youths wearing handkerchief masks, they made their way from the Shwedagon, a little out of central Rangoon, and dispersed in the heart of the capital at the 2,000-year-old Sul Pagoda. They shouted anti-government slogans and were joined by red-robed Buddhist monks and bands of industrial workers. There was no challenge to them. Security men kept out of sight and even the white-shirted traffic police, who do not carry arms, seemed to have disappeared.

Martial law did not deter demonstrators the next day. One local who witnessed a small rally noted that participants were not confrontational. Their only call was for a change in the government. As they passed they urged the crowd to clap if they agreed with the need to change. Everyone complied -- including some government officials present.

The violence began when the disturbances spread upconutry. There had already been reports of widespread protests outside Rangoon, but over the weekend of Aug. 6 and 7 came the first official news of deaths and injuries. Involved were the central Burma town of Yenangyaung, the port of Pegu 809 km northeast of the capital and nearby Thanatpin. By official count, five people were killed and an unknown number wounded when local police fired on the crowds to disperse them. Official reports say there were protests in fourteen towns and cities besides Rangoon, ranging from Myitkyina in the north to Mergui, 550 km southeast of Rangoon, though not all were named. In the former imperial capital of Mandalay, the country's second largest city, two people were reportedly shot dead. News of the rash of incidents seemed to boost the protest in Rangoon.

One reason the Aug. 8 demonstration did not begin bloodily was a shrewd move by the government to deflect discontent over soaring prices of foodstuffs. The authorities had begun sales of rice, cooking oil, salt and fish through cooperative units to keep prices down. This mainly benefitted low-income workers who might have been tempted to take their grievances to the streets. Another reason was that soldiers had replaced the dreaded lon-htain --riot police. "By using disciplined army troops to keep order, the government was able to keep the police, with their reputation for brutality, away from crowds to avoid aggravation of tensions," one analyst was quoted as saying. The lon-htain have been accused of torturing, killing and raping students in anti-government riots in March and June. Sein Lwin is particularly hated because he was in charge of the lon-htain before coming to power. The deployment of army troops brought its own problems. Visitors returning from Rangoon report "troubles" between soldiers Burma and non-Burman origin.

The protesting students seem to have won much public opinion to their cause. They have gained sympathy for their suffering at the hands of the authorities, often officially covered up, but most of all they have the agreement of many on their criticism of the government's economic ineptness. Protests have been joined by other sections of the public including Buddhist monks. The clergy, like the students, played a key role in the country's independence movement. They are highly respected in Burma, where 87% of the population of 38 million is Buddhist.

Interestingly, Sein Lwin's public relations machine has been making much of his devoutness. Each year, it is said, he makes merit with Buddhist monks on the anniversary of shooting of 22 students by soldiers of his old unit in pre Independence days. Another story of old times tells of how the leader, plagued by nightmares after personally beheading seven dacoits, went off to meditate. After two hours, he claimed he had cleansed his conscience of two faces disturbing his slumber and would return to rid himself of the others. The tale is apparently meant to show that he is not such a bad person after all.

The new president's future will depend much on his handling of students. "They are well-organised now, unlike last March when the protests were spontaneous," notes one Asian diplomat in Rangoon. Hand made posters and banners held by the youngsters today bear the symbol of a peacock in a circle, the insignia of the pro-Independence students' union to which Ne Win and other first generation leaders belonged. Ne Win's "Burmese Way to Socialism" -- a mix of militarism, Marxism and Buddhism -- has been blamed for pushing Burma to the brink of economic ruin and rousing student ire.

Sein Lwin, on the other hand, is holding out promises of economic reform. Soon after taking power, he announced new policies to exploit Burma's natural resources and revitalise its industry. Among them: fresh avenues for foreign investment, encouragement to private enterprise and joint ventures and legalisation of frontier trade. Indeed, last week, as demonstrations went on, the government signed a trade agreement with officials from China's Yunnan Province, which borders Burma. "Sein Lwin seems quite genuine about economic reforms," says one Rangoon-based Asian diplomat. "Of course, the Burmese think it's all eyewash." One Western diplomat, however, reckoned that "thinking Burmese" would be willing to give him a chance -- if only to avoid a bloodbath.

Sein Lwin was once said to have been described by Ne Win as "my necessary evil." Indeed, he is known as a man who is short on imagination but long on determination to tackle vexing problems. In Ne Win's monolithic administration, only the top man himself attracted attention. Many knew nothing about Sein Lwin beyond his image as the commandant of the lon-htain. Weeks after his installation, very little more has surfaced about the personal idiosyncrasies of Burma's new ruler, except that he is considered to be a workaholic and teetotaller, not sharing Ne Win's penchant for women and corruption. "He's got all the qualities that are different," notes one diplomat. Even so, these attributes may not be enough for Sein Lwin to revive Burma's sagging e4economy or to hold together acountry rebelling against his rule.

Significantly, no alternative has presented itself. The students are clearly dedicated to their cause -- stories have surfaced of youths baring their chests and taunting soldiers to shoot them and one Burmese source said 3,000 kamikaze students were believed to have declared a willingness to die if necessary. But they have not put forward any program for reform so far. their demands have been largely self-concerned -- the release of arrested students or the right to form a student union. But beyond those issues, the students' marching cries appeal to a spirit of nationalism -- and an anguished yearning for change.

ASIAWEEK/19 AUG 1988.