Asiaweek, 14 Oct. 1988

Going Back to Work, Sullenly

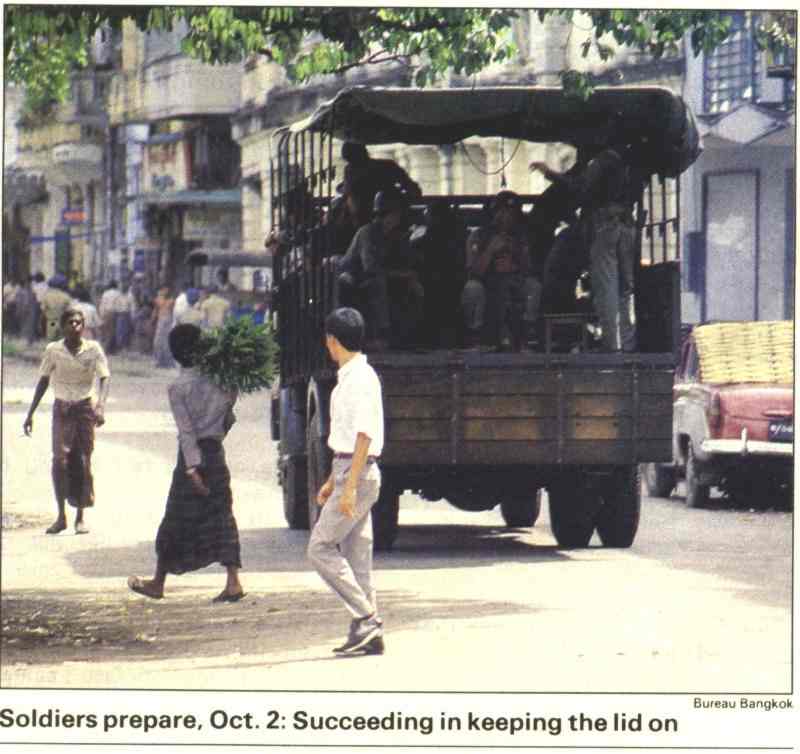

The heat and dust had taken its toll of the troops guarding key buildings in Rangoon. As the sun rose higher, soldiers sitting in parked army vehicles nodded off to sleep. Rifle-toting comrades patrolling the streets were obliged to be more alert. For beneath the apparent somnolence, there was a keen edge of tension. The heavy military presence was clearly intended to send a message: return to work, or else. For weeks, virtually the entire populace had been off the job, backing demands for democracy. That Monday, Oct. 3, marked the ruling military junta's deadline for an end to the general strike. The government had warned that those who stayed away would be dismissed or punished, while anyone who prevented them returning "will be dealt with sternly." To preempt any trouble, the authorities ringed the red-brack Hall of Ministers government complex in central Rangoon with armed troops. Nearby Anawrahta Street was lined with gleaming military hardware: anti-aircraft guns mounted on vehicles, armoured cars and armoured personnel carriers. Six snap rallies took place, but they quickly broke up as soon as army convoys approached. The only reported violent incident was a blast in a warehouse on downtown Merchant Street in which one soldier was wounded.

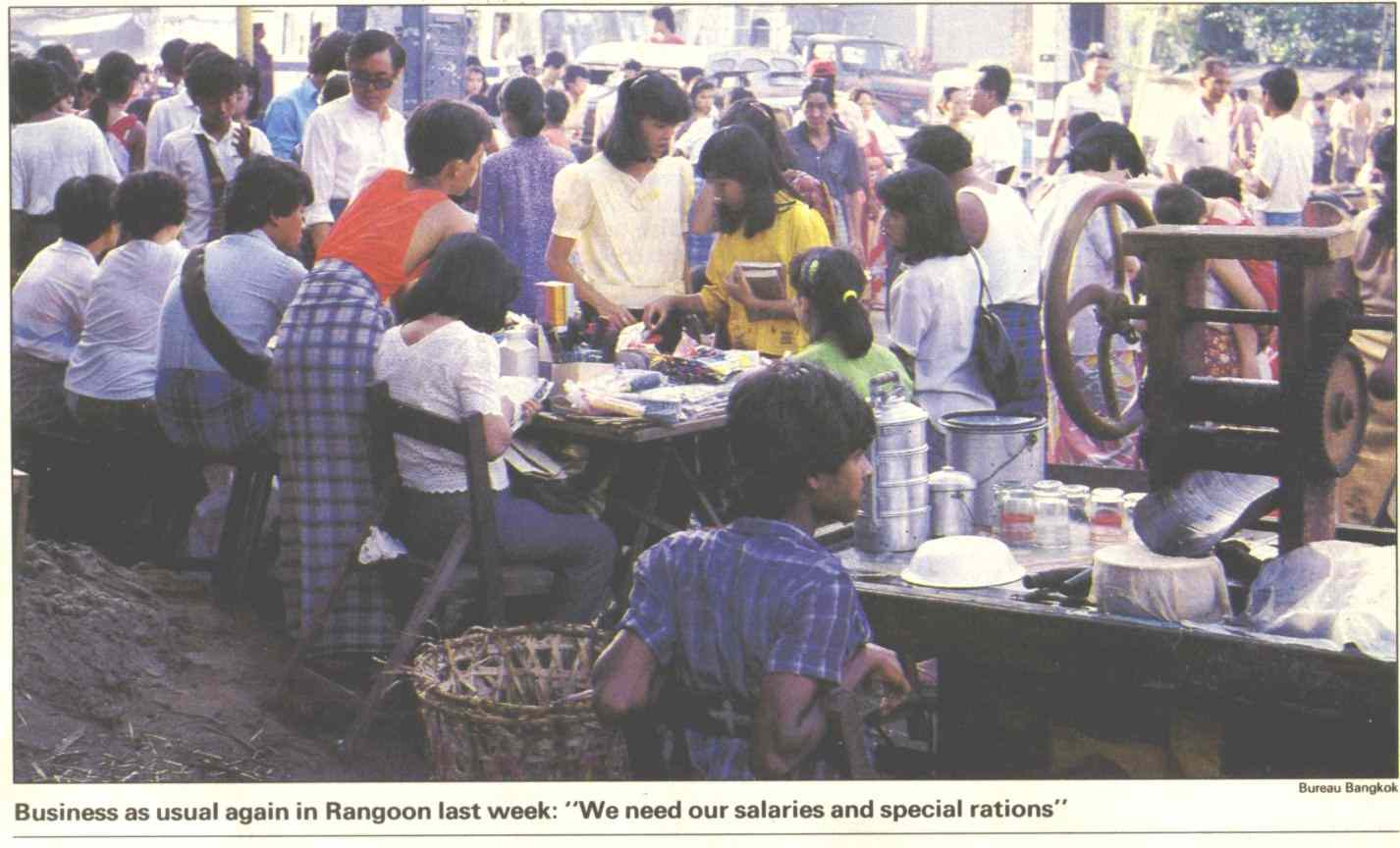

The stern official warnings had their effect: sullenly, most people seemed to have returned. No independent estimates were available, but the authorities claimed that more than 90 % of Rangoon's civil servants turned up for work on Monday. The attendance figures in townships were said to be even higher. Shops, banks and businesses were open and the hitherto deserted streets bustled with activity. Official accounts also claimed a 100 % back-to-work success in Mandalay, the former royal capital 600 km north of Rangoon. Sources said several senior personnel were either dismissed or pensioned for involvement in the strike, which for many workers had begun back on Aug. 8.

Many returnees, however, seemed simply to be attending office in order to collect September salaries and incentive rations, as other workers had done the week earlier. "We have to go back. We need money, our salaries and the special rations of rice and oil," one government clerk was quoted as saying. Indeed, some employees roamed idly through the streets after clocking in at work. Damaged equipment and a lack of raw materials meant virtually no work was done at offices and factories.

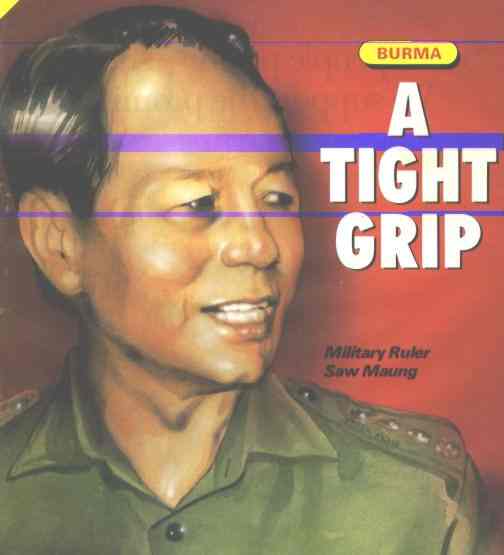

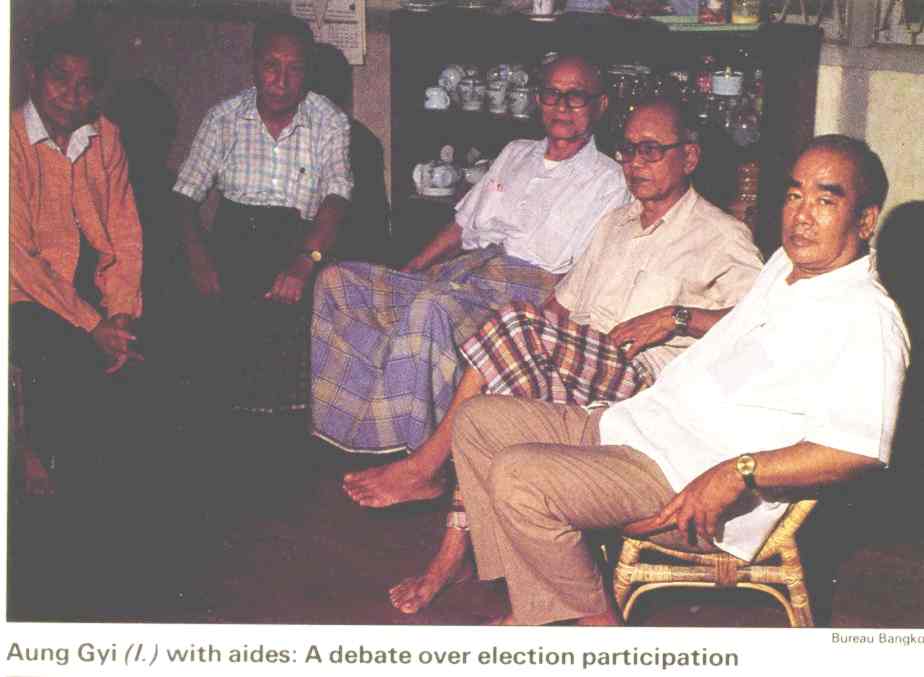

But that provided little solace to the disappointed pro-democracy forces. The had viewed the continuation of the boycott as crucial to their challenge to the military regime of Gen. Saw Maung, who outsete the civil administration of President Maung Maung in a Sept. 18 coup, and retired strongman Ne Win, widely believed still to be in control. The general strike, Burma's first mass labour protest in 26 years, had crippled essential services and brought administrative machinery to a standstill. The main opposition group, led by veteran dissident Aung Gyi and now know as the National League for Democracy (NLD), had urged strikers to stay away from work "by any feasible means" until democracy was achieved. The seven-week-old All Burma Students' Union had made a similar plea. "The blood of the people, students and monks is not dry yet," read an ABSU statement. "Let us not betray them and commit treason." But for now, it seemed, Saw Maung had succeeded in keeping the lid on.

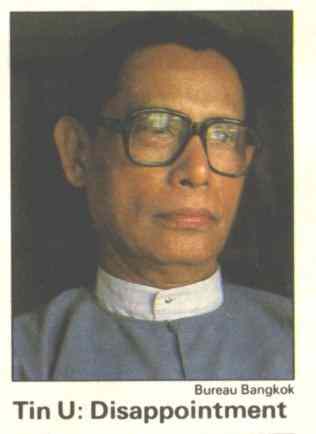

If the return-to-work failed to stick, however, Burma-watchers believed it would mean further disintegration of the shattered economy. That, they added, would force the government to open a dialogue with the opposition. NLD vice chairman Tin U said his party had already received a letter from the junta offering to meet with the opposition "in the near future." If the NLD talked with the regime, said Tin U, he would first ask for democratic rights to be given to the people. "I think they [the junta] will hold a meeting with us in order to find a good solution," he said.

The dissidents themselves appeared to be moving towards compromise. Last week, three opposition political groups registered with the military regime, One was the NLD. Another was the new People's Democratic Party, formed by Aung Than, brother of resistance hero Aung San and uncle of NLD general secretary Aung San Suu Kyi. The third was the Democracy Party, an offshoot of the League for Democracy and Peace (LDP) founded Aug. 29 by ex-premier U Nu (see interview.). All three, however, insisted they would not participate in proposed multi-party elections unless the government met certain conditions. Although these were not specified, observers reckoned they included free access to the media and credible methods of vote counting.

Yet the opposition's stand on the polls seemed fuzzy. Many analysts believed the dissidents were in fact dead set against participation but were going along with the process to be able to continue criticising the government without getting arrested. "Most of the opposition leaders won't participate [in an election]," said one seasoned Burmese observer. "They know it'll be rigged. For the moment, however, they are ostensibly taking part in the process as a means to voice their frustrations to the press and to the outside world."

Tin U echoed some of that thinking. "For the time being, we have to have an accommodation [with the government] in order to have legal status," he told Asiaweek in Rangoon. Nonetheless, the participation issue split the opposition. Last week LDP leader U Nu denounced as "traitors" all those who agreed to elections; later he cut his links to the Democracy Party because it had registered with the government. "We will have nothing to do with them [the military rulers]," he declared angrily. There appeared to be a difference of opinion within the top NLD echelons as well. Aung San Suu Kyi had originally opposed contesting the polls. But Tin U saw potential benefits. "If we don't stand for elections," he said, "then we cannot put any sort of representative in the assembly or Parliament. Our privileges, our opportunities will have been lost." However, he added that the party would stand for elections only "if democratic rights are truly observed."

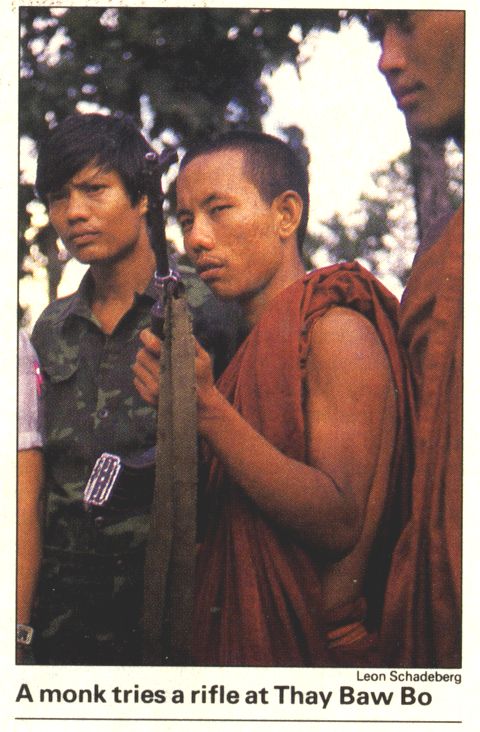

The polls talk also angered radical protesters. The post-coup crackdown sent thousands of students and monks fleeing to the jungled border regions controlled by various ethnic rebel groups. Reports said the insurgents were providing military training to the youngsters. So far, most of the students and monks have take refuge in Karen National Union bases, including Thay Baw Bo and Kler Day along the winding Moei river bordering Thailand. Analysts believed there was still little chance of students and insurgent forces scoring major military success against the battle-hardened Burmese Army. "This action has only strengthened the resolve of the army to fight the rebels," said a Thai-Burma scholar. But the border situation was heating up as the rainy season drew to a close. Heavy fighting between Rangoon troops and left guerillas continued last week around the northeastern town of Mong Yang in Shan State. Reports said 21 Burma Communist Party fighters had died in the offensive.

To Tin U, a retired general and former chief of the armed forces, the stepped up insurgent attacks meant trouble for Rangoon. "Because of the concentration of forces in the big cities, the forces around the frontier areas and remote areas have been lessened," he said. "Before, the population was with the government side, or neutral. But now, they are a little bit hostile to the army. Some have assisted the insurgents. Uprisings are coming up, and some places have been reoccupied by the insurgents."

Meanwhile, young people who remained behind in the capital have formed the Burma Revolutionary Force, an association of 51 student organisations, including radical elements from the Rangoon Institute of Technology and Rangoon University. The BRF claims a membership of 5,000 to 10,000 students with links across the country. Their strategy: "spontaneous" guerilla demonstrations in Rangoon for as long as it takes for the military to show up. One test run was made at the corner of Maha Bandoola Street on Saturday, Oct. 1. A group of students began a protest at about 10.45 a.m. but quickly dispersed after soldiers arrived.

Clearly worried by such defiance, the army has cracked down hardest on the youngsters. Soldiers were reportedly searching students' homes and intimidating their families. A Burmese source claimed that in southern Bassein town, arrested students were made to sit in the sun the wold day shouting "doh a-ye"("our rights"), their marching cry on the streets. He alleged that some were killed for as little as carrying a student card. The military have come down equally ruthlessly on suspected looters. In one incident in Rangoon, two men were caught pilfering from a ware house and were summarily executed. After being made to crowl on the ground, the first was cut down with a shot to the head; the other caught three bullets in the back. State-run radio announced on Oct. 4 that twelve looters had been shot dead by security forces in Rangoon. The killings brought the official death-toll since the coup to 441, but independent sources put the figure at more than 1,000.

The continuing security problem raised the crucial question: would elections be held ? To many observers, the picture appeared bleak. On Sept. 11, the People's Assembly had called for polls within three months. But coup leader Saw Maung later declared balloting would be held only when law and order was restored. "That," remarked one Burmese source, "could take forever." One of the five official election commissioners told Asiaweek the group believed next March would be the earliest feasible date; the cost, they estimated, could run to $7 million.

If elections did take place, many onlookers questioned whether they would be valid. "The new party [the government backed National Unity Party] will use all available state resources to spread propaganda illegally to the provinces," asserted an Asian diplomat posted in Rangoon. "The government still controls radio, the key media outlet. They will pound campaign messages to villagers, and opposition parties won't be given equal time or have any significant channel to voice their platforms." Indeed, Aung San Suu Kyi last week accused Burma's rulers of using state resources to organise grassroots support -- in clear violation, she said, of an election code issued just days earlier.

As always, however, most analysts believed genuine change would not occur in Burma until Ne Win exited the political scene. The ex-resident's name was not on the list of leaders of the National Unity Party, the new guise adopted by the long-serving Burma Socialist Program Party founded by him. But the 77-year-old leader was assumed still to be manipulating events. "I don't know of anyone who believes Saw Maung is running the country," said a Rangoon based diplomat. "Ne Win is still calling the shots." The elusive strongman has lived behind a thick security screen at his lakeside Rangoon villa for the past two months. Last week he was spotted by diplomats riding through the city in a blue-curtained Land Rover, peeping outside.

INTERVIEW/U NU

'I'm Know as a Rash Man'

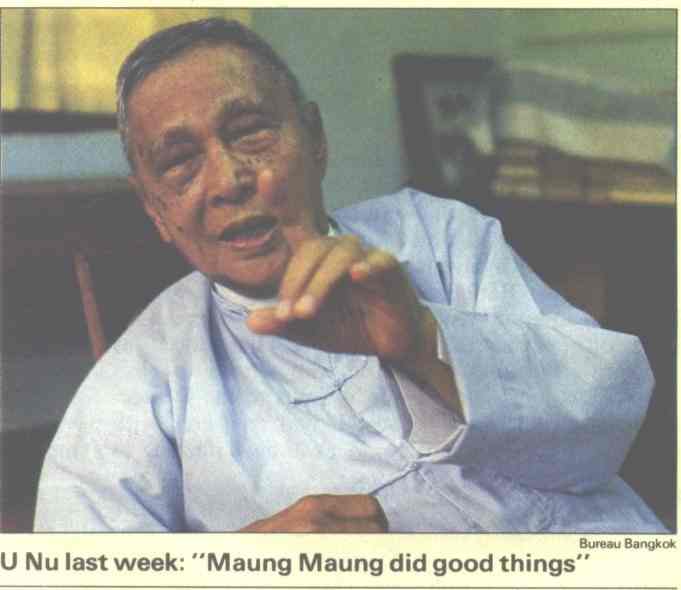

In recent weeks, popular protests in Burma has evolved into a coherent opposition force. It was veteran dissident U Nu, 81, who made the first attempt to constructively channel the anti-government unrest which swept Burma soon after the July 23 resignation of longtime strongman Ne Win. On Aug. 29, U Nu formed the League for Democracy and Peace (LDP) along with prominent opposition figure Tin U. Eleven days later, without consulting his comrades, U Nu announced a rival government to that of then-president Maung Maung. The move floundered when Tin U and other top leaders quit the LDP. Since then, Tin U has joined hands with dissidents Aung San Suu Kyi and Aung Gyi to form a separate alliance. U Nu has remained aloof.

A prominent resistance figure in his student days, U Nu became Burma's first prime minister after Independence in 1948. He served for ten years, with only a brief period out of office in 1956-57. Amid political chaos in 1958, he resigned in favour of Gen. Ne Win, who headed a "caretaker government" for two years before returning power to U Nu. But in 1962, Ne Win staged a putsch and threw U Nu in prison. After his release four years later, U Nu organised an anti-Ne Win movement along the Thailand-Burma border. When the movement failed, he settled down in India, returning to Burma in 1980 at Ne Win's invitation. An intelligent, learned man, U Nu is known for what one diplomat wryly termed "totally immovable flexibility." People say he is not well, but the veteran leader seemed healthy last week as he talked with an Asiaweek correspondent in a large room by the garden of his Rangoon residence. Excerpts:

When you formed a provisional government, some felt you hadn't done it very tactfully. Some groups of people very much wanted unity between me and the three other persons [dissidents Aung San Suu Kyi, Tin U and Aung Gyi] .. I proposed that if the trio wanted to join my party, they could. If they come to my party, since its program is laid by me, I would be the leader.

If I wanted to do a certain thing I do it at once, sometimes without consulting my comrades. But I always give them this chance: if they don't like what I do, I resign from the leadership. If they accept what I have done, they support me. In democracy that should be the way. But here I'm known as a very tactless man, a very rash man. Tactlessness is sometimes a crime, but it can be virtue also sometimes.

Do you think it's too late for the opposition, now that Ne Win has apparently reasserted himself ? I cannot actually wrest power form him as he wrested it from me. I know that for certain. But I want to make my constitutional position known to my people as well as those outside Burma to enhance my prestige as leader here. I am the constitutional prime minister. The other fellow [Ne Win] was not a constitutional leader. I am not only the constitutional leader but the one who got the majority overwhelming support from the people. It is a sort of picture of contrasts, you see.

Isn't the opposition's practical problem how to remove Ne Win ? We are going step by step. The moment I feel it is not practical I will abandon it. But at the moment I think this program is the only one that will suit us, suit the people.

Has it been worth it? Has the progress towards democracy been sufficient to justify the number of killings ? We're doing our best ... Before I took this stand, the people did not know how they should go forward. Now they know. Our goal will be none other than the holding of free and fair elections. Before the coup d'etat I was in favour of contesting polls set up by the government. At that time the majority of the country was not in favour of participating. They said they did not trust the government. I was alone in saying they should, that the elections would give us the solutions we needed because Maung Maung had done good things.

On the day he became the president, he withdrew the military government and he officially declared that people demonstrating peacefully would not be shot. [Later he agreed] there would be no referendum [on a multi-party system] and they would go directly to free and fair elections. Those were good points, so I to the people: he's a good man, he's not bluffing. Moreover, maung Maung appointed a very reliable election commission. Out of five, I could blindly accept four members without any argument. with such people in the commission, I said, there was a very good chance for us to get power by contesting the elections. but since the coup detat, my mind has changed. I do not trust these people [the military regime]... If they[the dissident trio] agree to not participate in the coming elections there are chances of our [working] together. I for one will not allow those who support me to participate in the elections as long as the militarists, who have shot down not less than 2,000 school children, are in power.

People outside felt Maung Maung was part of the same ruling clique. No, no, no. Outside people were wrong. They should know that in a country like this elections would take some time.

What do you think will happen now ? I am not a prophet. Ican't tell you. You tell me. ... Thing are moving very fast. I cannot even say what will happen after two days.

ASIAWEEK/ 14 OCTOBER 1988.