Asiaweek, 21 October 1988

Debating the Polls Promise

For several days, Rangoon's gamblers had swamped downtown Maha Bandoola Street, eagerly staking kyats on the games of chance being clandestinely played on the pavement. The roadside betting did not last long. The authorities soon ordered crackdown, following that up with a pointed editorial in the state-controlled Working People's Daily on the evils of gambling. Even official disapproval, however, failed to deter many Burmese from wagering huge sums of money on the outcome of an astrological prediction. According to the stars, Gen. Saw Maung, who seized power in a putsch last month, would be ousted on Oct. 18. But a similar forecast made for the last week of September had not come true. And with the army still firmly in control, it seemed likely that Saw Maung would yet again prove the soothsayers wrong.

Indeed, after weeks of protest and thousands of deaths, anti-government forces seemed almost back to where they had started from in July, when longtime strongman Ne Win officially stepped down. An authoritarian regime loyal to Ne Win was still in power, and prospects for a shift to democracy remained murky. The only thing the dissidents had gained was a nebulous promise by the government for multi-party national polls. A five-man elections commission had been appointed by civilian president Maung Maung to work out the details, and it had been retained by Saw Maung after Maung Maung's ouster.

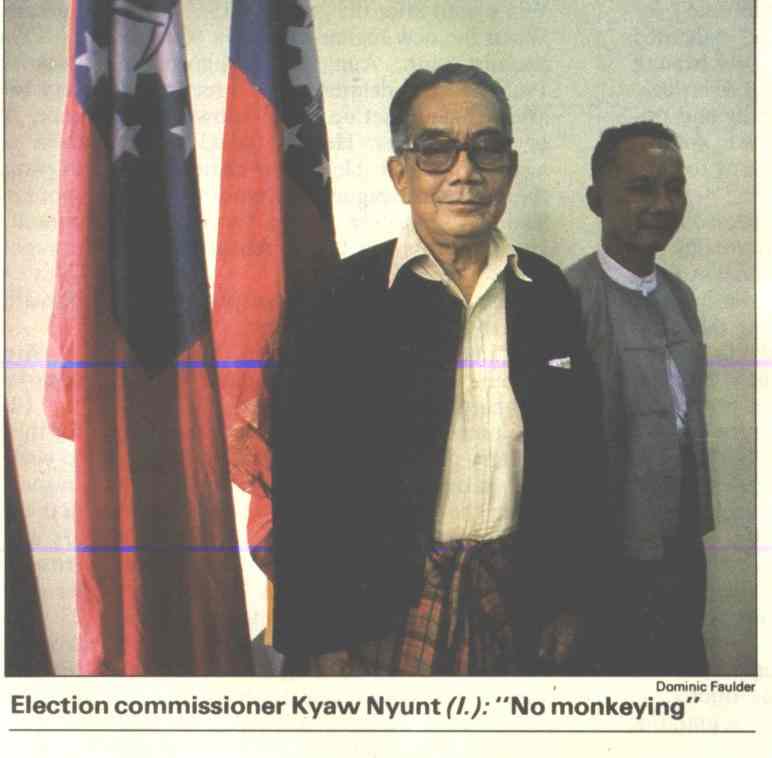

Few analysts doubted the integrity of the members of poll body, but most agreed it lacked teeth. According to commission member Kyaw Nuynt, 72, the government would be advised to loosen its hold on the media and give the opposition equal time on state-run radio and television. But he conceded that the commission had no real powers to intervene. "We can only tell the government what we require," he told Asiaweek in Rangoon. "It must give us all the supporting services towards speedily holding free and fair elections." For the dissidents, that was precisely the issue. How valid would the proposed polls be ? Noted Aung San Suu Kyi, general secretary of the opposition National League for Democracy(NLD): "I don't think that this government will willingly create free and fair elections."

Kyaw Nyunt insisted that was not so. "There'sll be no monkeying with the results," he said. "As soon as polling is closed, all ballots boxes will be opened then and there, in the presence of candidates or their representatives and local respectable people such as leaders students or sanghas [Buddhist clergy]." He said polling stations would be staffed by civil servants without political connections, who would be assisted by local elders. Elections would be nationwide, he added, "except for a few marginal areas under the control of insurgent groups." More than a dozen rebel Burmese minorities operate along the borders with Thailand and China. Under the election code, they are barred from registering with the commission.

The military regime has so far recognised nine political organisations, the most potent being the NLD led by key opposition figure Aung Gyi. He believes elections are bound to take place (see interview, p. 30). Among six groups authorised last week were two formed by oldtime leftist leaders, as well as the revived Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League headed by ex-parliamentarian Bo Kya Myunt and Cho Cho Kyaw Nyein. The latter is daughter of Kyaw Nyein, a former deputy to prime minister U Nu, whom Ne Win over threw in a coup in 1962. U Nu has remained steadfast in his opposition to participation. Interestingly, one organisation that had not registered with the commission was the government-backed National Unity Party (NUP), the new incarnation of the Burma Socialist Program Party founded by Ne Win. Under the election law, the NUP has to divest itself of state-related holdings. But reports said that was proving difficult for the NUP because the erstwhile BSPP held substantial amounts of real estate and other fixed assets. Even shorn of its wealth, however, the NUP/BSPP organisation would still be formidable in an election.

None of the dissident groups have actually agreed to contest the polls, however. NLD leaders, for example, have repeatedly stressed that participation would be dependent on the formation of an interim government and on restoration of democratic rights. According to Aung San Suu Kyi, daughter of resistance hero Aung San, the NLD had registered only to have some kind of legal umbrella under whicdh the scattered opposition forces could unite. Students, too, were staying largely on the safe side of the line. Last week 70% of the 119 members of the executive committee of the All Burma Federation of Students' Unions opted for achieving democracy through legal means. The decision included registering as a party with the elections commission. The remaining 30% said they would continue clandestine anti-government activities. The ABFSU estimated there were some 4,000 students underground in Rangoon while another 8,000 were with the rebels, mostly along the Thai-Burma border.

Federation spokesman Ye Naing Aung, an executive committee member, said the students planned no direct confrontation with the military in the near future, although it was possible small radical factions might try something on their own. "We do not want to fight the government by armed struggle," said Ye Naing Aung (a nom de guerre meaning "Valiant Victory"). "We now have two options. One is armed struggle. The other is legal means. We prefer the second one. So we have to form a party." He said the ABFSU had not yet decided on participating in the polls. As analysts saw it, however, the crucial issue for the "70% faction" was whether the government would permit it to register. Observers reckoned that the recognition last week of the People's Youth Federation (Burma) and the All Burma United Youth Organisation was an attempt by the government to pre-empt activist students. Both fledgling youth groups were believed to have strong links to the NUP.

Still to be seen was when polls could be held. Coup leader Saw Maung had declared balloting would be held only after law and order was restored. Commission member Kyaw Nyunt expected March would be the "soonest possible date" for staging the elections, which he estimated would cost $7 million. "Gen. Saw Maung is not dragging his feet," he told Asiaweek. "He has already said both openly and privately that what he is doing now is holding a hot potato and he doesn't want to prolong the agony."

In other sphere, Burma seemed to be limping back to a measure of normalcy last week. Rice prices had begun to fall in Rangoon. It was business as usual again for the city's hawkers and blackmarketeers. But essential goods such as petrol and edible oils were scarce. Despite the heavy military presence, sporadic looting of warehouses was reportedly continuing. The few brief "snap rallies" that had flared earlier were rarer. "Burma is smouldering at the moment," one diplomat was quoted as saying. "The army has won this round, but people are very, very angry."

Ahead were new potential flash-points. The health of Aung San Suu Kyi's bedridden mother, Khin Kyi, widow of Aung San, was said to be failing. Observers believed her death could recharge popular protest in much the same way as the funeral of respected Burmese U.N. secretary-general U Thant had done in 1974. The capital was also abuzz with talk that Ne Win was planning a trip to Austria for medical treatment. But although he has made such trips regularly in the past, analysts questioned whether the enigmatic strongman would leave the country at such a critical juncture. Of more immediate worry to Burma's dissidents were rumours that Saw Maung was drawing flak from hardliners in the army. The charge: being too lenient on the opposition.

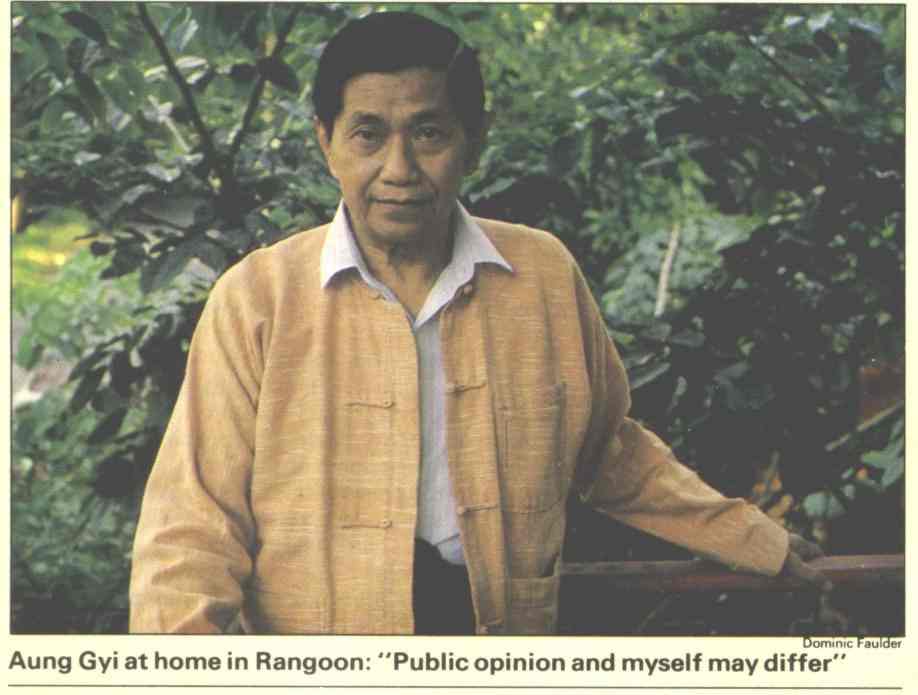

INTERVIEW/AUNG GYI

'Ne Win Wants an Election'

Much of the groundwork for the dramatic events in Burma of the past three months was laid by retired brigadier-general Aung Gyi. His letters to strongman Ne Win criticising the state of the economy and detailing atrocities during student riots were widely circulated. In early July, Ne Win had four of the letters in front of him when he gave a severe dressing-down to several aides (Asiaweek, Aug. 12). Now 70, Aung Gyi was a key lieutenant of Ne Win's until after the general's 1962 coup. When the new regime charted a strongly socialist path, Aung Gyi resigned. In 1965 he was detained for three years, after which he set up a well-known chain of coffee shops. He was jailed briefly again in August. He is now chairman of the National League for Democracy, the leading opposition group formed with key dissidents Tin U and Aung San Suu Kyi.

Aung Gyi still faces suspicion, particularly among students, for his longtime links with Ne Win. Early this month, Aung Gyi left Rangoon for the northern town of Maymyo by road. Diplomatic sources confirmed that the military government of Gen. Saw Maung had provided him with scarce fuel to make the trip. He was also permitted to make speeches along the way, including in the towns of Pegu, Meiktila and Pyinmana. Aung Gyi says he does not know Saw Maung personally, but he make no bones about his affinity with Ne Win. "I am reading his mind," he says. "We have been together for so many years. As army personnel, we have to read the opposition general's mind, how it works." Just before his Maymyo trip, Aung Spoke with Asiaweek's Dominic FAulder in Rangoon. Excerpts from the conversation:

How do you see the situation now?

My personal impression is that we are bound to face elections one way or the other. I think the present situation is quite favourable. for the army itself, [running the country] is a very big burden. There is no foreign exchange, and all international organisations, including banks, the Japanese government and the American government, have given very strong warnings -- they've even condemned our military government. So there is no chance of getting aid or grants any more. Our economic situation is in such bad shape, we'll have no foreign exchange in 1989. I don't think there's any chance of exporting anything. That means zero-minus conditions -- $4 million minus. All our country has been destroyed by hooligans. All the raw materials are gone. The rail transport is just negligible. With all these difficulties, I don't think any military authorities want to take the responsibility.

But some would says the economy of Burma has been closet to rack-bottom for a very long time?

The real impact has come only now. Because we are Buddhist people, we are very tolerant. Now it's beyond our tolerance. All of a sudden ... because of all these economic troubles and people's intolerance, the whole country has spontaneously risen to challenge Ne Win himself. So Ne Win after deliberation thought he couldn't carry on anymore. That's why he quit totally -- and I think he really meant it.

Are you suggesting that Ne Win is out of the picture?

I have been associated with Ne Win for the last 40 years and we are very closet to each other -- we are complementary. In social life, he is like my godfather, but in the political [sphere] we are contemporary and can more or less speak on equal terms. Since 1965, I have written [him] letter after letter. I cirticised throughtout the 23 years, but he didn't think it was very serious. Their real impact came between March and July. [One missive, written in May,] we call the "41-page letter." Only then was he shocked, when he saw how critical our economic situation is and how our economy has been damaged when we compare it with Thailand's. Throughout, all the subordinates had given a very rosy picture -- every four year plan was successful up to the last moment. All of a sudden he realised that all these thing were just nonsense.

Asiaweek carried an account of how on your way to Australia last year you flew to Bangkok, and you were so shocked by what a modern, powerful city it had become that you wept in your hotel room.

Yes, that is true.

But Ne Win has been going abroad for 26 years. He has know all along.

This is the difference between Gen. Ne Win and myself. When Ne Win visited, it was like sightseeing. He never went to the root, never studied the real troubles in the Burmese economy. Since 1937 as a student, I have been a politician. Economy is my line, so I feel it. When I stepped down from the plane [in Bangkok], what I saw struck my heart. I didn't realise there was such a vast difference between Thailand and our country. It was so vast -- I couldn't control myslef.

Isn't Ne Win responsible?

The overall policy failure is Gen. Ne Win's responsibility. But executive responsibility should be with San Yu [who resigned as president in July] and all the prime ministers. Ne Win relied for every thing on his lieutenants. He is not a real administrator; all the economic planning has been carried out by his subordinates.

For the last 26 years he was reading all these false inflated figures and he thought everything was working. But all of a sudden when he got my "41" letter, only then -- he was so shocked. And then after that [came the student riots]. Gen. Ne Win only knew that two persons were killed. He didn't go outside -- he's very isolated. He had to believe the reports he got. But when I worte about all these atrocities, that even rape was included, he made enquiries himself and [found that] what I wrote was correct. The economy on one side, and then the human rights violations, these things combined, he couldn't tolerate it.

So he decided to quit. He said, "This one-party system is hopeless. They exercise too much power. They shut every eye and every moutn." He was so agitated. He decided to abolish it. The words he used [calling for a multi-party system in July] were not mine. It is his conviction. In this matter, public opinion and myself may differ. The public doesn't [have] trust anymore. They know Ne Win was very powerful so they think he was behind all these things ...

When Ne Win saw Sein Lwin's presidency ruthlessly kill a lot of students -- in Rangoon alone, small children of about 11-13 -- when he knew that, he just called Sein Lwin and kicked him out. He asked Maung Maung to carry on and asked him to prepare for democratic elections.

That was definitely Ne Win's decision?

Only he can do that. though he quits all these presidencies and chairmanships, the army is still very loyal to him. Since Independence, he has been the prime father-like figure in the army. I was deputy [chief of staff] and I know their mentality. He still controlled the army. So when Maung Maung's works failed -- because a lot of rioters and all these hooligans came and looted all these things -- he decided the army should take over and suppress it. The he told the army, "As soon as possible you must have free and fair elections." That is what I wanted. That is the assignment he gave to Saw Maung.

So he also ordered the coup. Yet the result was a bloodbath. We don't know how many people were killed.

Well, I think in this military coup the casualties won't be more than 500 in Rangoon. But the previous August, all those killed in the Rangoon area [may total] about four or five thousand. That is my estimate. In August in the whole country I think it may be around 8,000 people.

What does Ne Win feel now?

Ne Win wants to see that an election is carried out very quickly, and then he wants the army to quit quickly and take their old previous line. The army should stay in the barracks.

A lot of things are being written at the moment about Ne Win's daughter, Khin Sanda Win. She has been accused of masterminding atrocities. Are the stories true?

Ne Win is not very well, so all the fingers pointed at Sanda Win. Sanda Win is like my daughter. She was brought up on my knee. I don't think such an intelligent and such a professional, educated lady as Sanda Win is cruel. This is unbelievable. Of course, there are some intelligence people in junior echelons, they may have used [the hallucinogenic drug] LSD and all these nasty things [against the demonstrators], and then a lot of beheadings were carried out. So I personally wrote to Gen. Saw Maung, "Gen. Saw Maung, we are not barbarians. This task is barbarous. Whoever it may be they should stop all this, and then from our side we will control the beheadings." Since that day, whether it is coincidence or not, it just stopped.

Do you think Ne Win or Sanda Win would talk to the outside world?

I don't think they will come directly into politics. They will stay aloof. And after their so-called mission, the multiparty system is established, then they may think their mission is accomplished. Only then will Ne Win quit, or he will stay behind. [Whether] his family will go out or not, that is [not clear].

Ne Win's place in history is often mentioned. Yet he is so little understood because he never explains anything to his own people. It is very peculiar. Burma as a whole is very peculiar. You know, nobody outside Burma can believe how such tolerant people all of a sudden burst like atomic bombs. Burma is such a place. Especially Gen. Ne Win's character. We don't know what is actually in his mind.

ASIAWEEK/ 21 OCTOBER 1988.